Mass timber — already celebrated for its sustainability and aesthetics — could soon have a surprising new role in healthcare: fighting harmful bacteria. That’s according to new research from the University of Oregon, which found that exposed wood may have antimicrobial benefits when used in hospital settings.

In a study funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Wood Innovations program, researchers discovered that when wood blocks were briefly wetted, they tested lower for bacterial levels than a plastic enclosure used as a control.

“People generally think of wood as unhygienic in a medical setting,” said Mark Fretz, assistant professor and co-director of the University of Oregon’s Institute for Health in the Built Environment, who led the research. “But wood actually transfers microbes at a lower rate than other less porous materials such as stainless steel.”

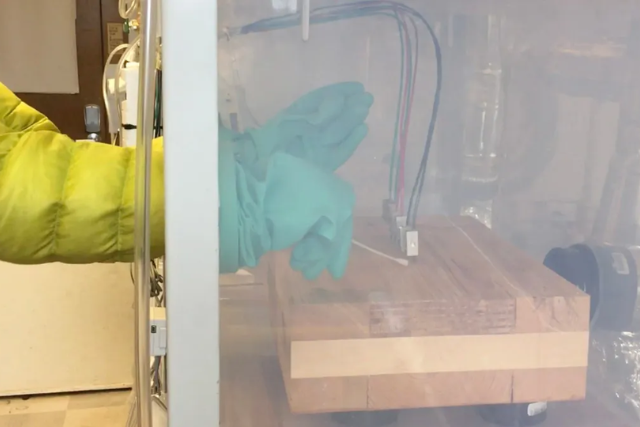

The research team, which also included scientists from Portland State University and the Salk Institute for Biological Studies in San Diego, tested blocks of cross-laminated timber (CLT), a popular mass timber component. They sealed the blocks in disinfected plastic boxes to mimic a hospital microenvironment — controlling humidity, air exchange, and temperature to match hospital building codes.

To recreate real-world conditions, they sprayed the blocks with tap water under three scenarios: once, daily for a week, and daily for four weeks. They then inoculated the blocks with a cocktail of microbes commonly found in hospitals and compared them to an empty plastic control box over four months.

“We wanted to explore how mass timber would stand up to the everyday rigors of healthcare settings,” said Gwynne Mhuireach, a research assistant professor at the University of Oregon. “In hospitals and clinics, germs are always present and surfaces occasionally get wet.”

The results were promising: except for the first two weeks after inoculation, the empty plastic control had greater viable microbial abundance than the wetted wood samples. The researchers believe wood’s natural pores and chemical compounds help trap or inhibit bacteria.

“Wood can release compounds called terpenes, many of which smell pleasant and inhibit microbial growth,” Fretz noted. The emissions of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) — which affect air quality and odors — also plateaued after wetting, suggesting that wood’s chemical emissions may play a role in curbing pathogens, Mhuireach added.

Despite these benefits, wood is rarely exposed in healthcare environments — mostly due to building codes and concerns about hygiene that the research team says are often outdated.

Already, however, one North American hospital is testing this theory at scale. The Prince Edward County Memorial Hospital in Picton, Ontario, will become the continent’s first un-encapsulated mass timber hospital when it opens, according to Quinte Health, the hospital network that operates the facility.

Still, many architects and health officials remain cautious. Fretz hopes their research will shift the perception of wood as “unhygienic” and encourage more exploration of natural materials in sterile medical environments.

For now, the study marks an early but compelling step toward rethinking how natural building materials can promote healthier indoor environments — even in places where sterility is paramount.

Originally reported by Matthew Thibault in Construction Dive.